by Colin Liddell

It is hard to say exactly how David Bowie will be remembered, as he was defined by his ability to constantly reinvent himself, both musically and visually.

Floppy-haired hippy, musical mime artist, Ziggy, Aladdin, the plastic soulster, the Thin White Duke, the Berlin kraut rocker, and funky New Romantic godfather — the list of chameleon styles and personas is long and colourful. But what is the essence of this abundance of creativity? The constant factor seems to be a rootless and restless sensibility that was both a response to the commercial drives of the music business and a resonance with Bowie’s own soul and psyche.

No doubt, psychiatrists can dig deep and find special reasons for this, but few are interested in mental eccentricity for its own sake. The key point is that whatever drove Bowie to be Bowie, Bowie himself became a symbol of his times, a type that encapsulated the age and became an avatar for all the less talented people who felt themselves pulled in as many directions as he was.

Bowie, when all is said and done, was a psychic photograph of post-war Britain, a country that, like Bowie, lacked a clear-cut sense of identity in more ways than one, including racially, culturally, and, at times, sexually. Dean Acheson’s famous quote that “Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role,” can also be read as a fashion statement and a description of the ever-changing pop charts.

With this in mind, it is intriguing that Bowie was born in 1947, the year in which the British Empire effectively died, following the independence of India. This ended the role the nation had been building to and playing for 250 years.

Interestingly, the year of his death — 2016 — could mark another important watershed, with many analysts expecting an in-out vote on EU membership to take place this year, possibly ending the most significant role the nation sought for itself in the wake of Acheson’s comment.

Like Bowie, Britain has been subjected to various influences and centres of gravity — the pull from America, the attraction of Europe, a dangerous enticement towards the exotic; all with a sense of Britain itself lacking any firm anchor.

The thrusting, dynamic, Promethean spirit of Britain, that which did so much to shape the world, did not disappear overnight. As the nation underwent relative decline from the 1880s onwards, there was an increasing awareness of British society’s defects and deficiencies, and an attempt to redress them.

One unsuspected strand in a country that, to outsiders, looks so staid and traditional was a drive toward radical modernization. The WWI Tank, the proto-blitzkrieg theories of Basil Liddell Hart, Frank Whittle’s jet engine, the hovercraft, the Concorde supersonic airliner, Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s “White heat of technology,” Sir Clive Sinclair’s ill-fated C5 electric car — even Dr. Who and the Daleks, and the horrifying concrete monstrosities of 1960s urban redevelopment — were all part of a temporal revanchist desire to once more be at the cutting edge of progress.

Here was a country where modernity was a secret fetish behind the twitching lace curtains of Victorian terraced housing, and this was something the young Bowie latched onto, after serving the usual apprenticeship trawling American rock n’ roll and a less conventional one exploring European influences, like the music of the Belgian chanson singer Jacque Brel.

While his early music was largely ignored by the British public, “Space Oddity,” a well-timed (1969) paean to the heroes of the ongoing space race resonated with the British fetish for modernity.

Bowie’s subsequent career continued to mine this rich seam, with futuristic songs like “Life on Mars” from the 1971 album Hunky Dory, and “Five Years,” “Moonage Daydream,” and “Starman” from 1972’s Ziggy Stardust album — as well as his eerie role some years later in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, a story that also uncovered a deep unease in Britain’s relationship with America.

In that movie, Bowie played the alien of the title role as a kind of out-of-water Englishmen, stranded in the extremely shallow waters of a materialistic, commercial, and alienating American culture. One is somewhat reminded of Stanley Kubrick’s counterpoint of the urbane academic James Mason and the crass American landlady Shelly Winters in the 1962 film Lolita, which explores a similar vector of transatlantic unease.

Bowie’s music also took on strong Nietzschean elements which flowed backwards through the European cultural canon into Faustian themes. Something similar was going on contemporaneously in the painting of Francis Bacon, whose subjects figuratively made a devil’s bargain, stretched out as they were on the Nietzschean tightrope “between figurative painting and abstraction.”

This Faustian aspect added poignancy to Bowie’s futuristic songs, raising them above the more visceral “space rock” jams of Hawkwind and Pink Floyd. For a country with no space program, it seems that there was an awful lot of space-related rock in the UK.

However, the Faustian element could also infuse the increasingly autobiographical tales of rock n’ roll excess that defined Bowie’s rockist projection, “Ziggy Stardust.” In the myth of Ziggy we see Bowie starting to feed on himself, an analogy for what was going on in a post-Empire Britain excluded from the Common Market (the forerunner of the present-day EU) by French jealousy.

This point may sound somewhat contrived, but it is also revealing that, following Britain’s admission to the Common Market in 1973 and the referendum confirming this in 1975, Bowie’s music and interests took a marked turn towards the European continent, mimicking Britain’s own trajectory.

In 1976 Bowie moved to Switzerland, and later the same year to Berlin. Before this he had been living in America, but the Thin White Duke character that this generated was a more aggressive version of the extraterrestrial he portrayed in The Man Who Fell to Earth, representing a sense of continuing alienation and dissatisfaction with America as the epitome of the West.

It was also around this time that Bowie was most effusive in his support for Fascism, collecting Nazi paraphernalia and making statements that “Britain could benefit from a Fascist leader.”

Britain’s embrace of a European identity in the mid-1970s was, on a meta-level, a partial rejection of a weakened America and its associated political system of liberal democracy. This lasted until corrective forces came into play, which they did in Bowie’s case with the Leftward politicization of rock music from 1976 onwards through the establishment of movements like Rock Against Racism. This was widely supported by the music press — papers like the NME, Sounds, and Melody Maker — as well as the political establishment, marking an alliance between the mainstream culture and the supposed counter-culture.

Bowie’s fascination with European fascism was thereafter quickly sublimated into the experimentation, alienation, and glacial eeriness of his Berlin Trilogy, the lyrics of which tended towards more anodyne sentiments as in “Be My Wife,” “Heroes,” and “DJ,” the last of which hints at Bowie’s decision to focus on the music and distance himself from controversial statements:

But Bowie’s odyssey was far from over. While the 1970s represented the post-Vietnam weakness of America and the rise of European potentialities, the Eighties marked a revival of American power and influence and a return to its musical tastes and value system, which exerted a strong pull on Bowie’s particular brand of rootlessness.

The Reaganomics of America were echoed by the Thatcherism of Britain, and both countries shared a yuppie culture that was essentially economically centre-right and culturally hard left. There was an increasing emphasis on an inclusive globalist culture, as seen in the “Live Aid” phenomenon, in which Bowie participated, prefiguring in a sense his second marriage to a model from the Horn of Africa.

Bowie’s 1980s albums, especially Let’s Dance, saw him getting heavily into funk, bringing in Nile Rodgers as producer, and embracing the culturally leftist narratives of “one worldism” and boosting the underdog, then common in pop and rock music. This is made clear in the video for the album’s title track, in which its Aboriginal characters are treated sympathetically as they struggle with the world imposed by the White man.

The song “China Girl,” written several years before, plays with fascistic tropes — “I stumble into town just like a sacred cow, visions of swastikas in my head, plans for everyone” — but is replete with self-serving irony, as swastikas are a common sight in the East, being both a Hindu and Buddhist symbol. The song then glamorizes Red China chic while promoting miscegenation.

From this album onwards, Bowie’s significance as a major musical artist declined, but with his Somalian wife (married 1992) and half-Black daughter (born 2002), we see Bowie again echoing other forces acting on Britain and other themes being played out, namely the forces of mass immigration, miscegenation, and increasing marginalization of Whites.

With Bowie’s death, his legacy and his wealth effectively falls into the hands of aliens, emphasising yet again the rootlessness of a Britain that, like Bowie, has gone through a myriad of changes in the last few decades.

Floppy-haired hippy, musical mime artist, Ziggy, Aladdin, the plastic soulster, the Thin White Duke, the Berlin kraut rocker, and funky New Romantic godfather — the list of chameleon styles and personas is long and colourful. But what is the essence of this abundance of creativity? The constant factor seems to be a rootless and restless sensibility that was both a response to the commercial drives of the music business and a resonance with Bowie’s own soul and psyche.

No doubt, psychiatrists can dig deep and find special reasons for this, but few are interested in mental eccentricity for its own sake. The key point is that whatever drove Bowie to be Bowie, Bowie himself became a symbol of his times, a type that encapsulated the age and became an avatar for all the less talented people who felt themselves pulled in as many directions as he was.

Bowie, when all is said and done, was a psychic photograph of post-war Britain, a country that, like Bowie, lacked a clear-cut sense of identity in more ways than one, including racially, culturally, and, at times, sexually. Dean Acheson’s famous quote that “Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role,” can also be read as a fashion statement and a description of the ever-changing pop charts.

With this in mind, it is intriguing that Bowie was born in 1947, the year in which the British Empire effectively died, following the independence of India. This ended the role the nation had been building to and playing for 250 years.

Interestingly, the year of his death — 2016 — could mark another important watershed, with many analysts expecting an in-out vote on EU membership to take place this year, possibly ending the most significant role the nation sought for itself in the wake of Acheson’s comment.

Like Bowie, Britain has been subjected to various influences and centres of gravity — the pull from America, the attraction of Europe, a dangerous enticement towards the exotic; all with a sense of Britain itself lacking any firm anchor.

The thrusting, dynamic, Promethean spirit of Britain, that which did so much to shape the world, did not disappear overnight. As the nation underwent relative decline from the 1880s onwards, there was an increasing awareness of British society’s defects and deficiencies, and an attempt to redress them.

One unsuspected strand in a country that, to outsiders, looks so staid and traditional was a drive toward radical modernization. The WWI Tank, the proto-blitzkrieg theories of Basil Liddell Hart, Frank Whittle’s jet engine, the hovercraft, the Concorde supersonic airliner, Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s “White heat of technology,” Sir Clive Sinclair’s ill-fated C5 electric car — even Dr. Who and the Daleks, and the horrifying concrete monstrosities of 1960s urban redevelopment — were all part of a temporal revanchist desire to once more be at the cutting edge of progress.

|

| Blake's Seven: British futureworld |

While his early music was largely ignored by the British public, “Space Oddity,” a well-timed (1969) paean to the heroes of the ongoing space race resonated with the British fetish for modernity.

Bowie’s subsequent career continued to mine this rich seam, with futuristic songs like “Life on Mars” from the 1971 album Hunky Dory, and “Five Years,” “Moonage Daydream,” and “Starman” from 1972’s Ziggy Stardust album — as well as his eerie role some years later in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, a story that also uncovered a deep unease in Britain’s relationship with America.

In that movie, Bowie played the alien of the title role as a kind of out-of-water Englishmen, stranded in the extremely shallow waters of a materialistic, commercial, and alienating American culture. One is somewhat reminded of Stanley Kubrick’s counterpoint of the urbane academic James Mason and the crass American landlady Shelly Winters in the 1962 film Lolita, which explores a similar vector of transatlantic unease.

|

| Bacon's art exploring the Nietzschean abyss |

This Faustian aspect added poignancy to Bowie’s futuristic songs, raising them above the more visceral “space rock” jams of Hawkwind and Pink Floyd. For a country with no space program, it seems that there was an awful lot of space-related rock in the UK.

However, the Faustian element could also infuse the increasingly autobiographical tales of rock n’ roll excess that defined Bowie’s rockist projection, “Ziggy Stardust.” In the myth of Ziggy we see Bowie starting to feed on himself, an analogy for what was going on in a post-Empire Britain excluded from the Common Market (the forerunner of the present-day EU) by French jealousy.

This point may sound somewhat contrived, but it is also revealing that, following Britain’s admission to the Common Market in 1973 and the referendum confirming this in 1975, Bowie’s music and interests took a marked turn towards the European continent, mimicking Britain’s own trajectory.

In 1976 Bowie moved to Switzerland, and later the same year to Berlin. Before this he had been living in America, but the Thin White Duke character that this generated was a more aggressive version of the extraterrestrial he portrayed in The Man Who Fell to Earth, representing a sense of continuing alienation and dissatisfaction with America as the epitome of the West.

It was also around this time that Bowie was most effusive in his support for Fascism, collecting Nazi paraphernalia and making statements that “Britain could benefit from a Fascist leader.”

Britain’s embrace of a European identity in the mid-1970s was, on a meta-level, a partial rejection of a weakened America and its associated political system of liberal democracy. This lasted until corrective forces came into play, which they did in Bowie’s case with the Leftward politicization of rock music from 1976 onwards through the establishment of movements like Rock Against Racism. This was widely supported by the music press — papers like the NME, Sounds, and Melody Maker — as well as the political establishment, marking an alliance between the mainstream culture and the supposed counter-culture.

Bowie’s fascination with European fascism was thereafter quickly sublimated into the experimentation, alienation, and glacial eeriness of his Berlin Trilogy, the lyrics of which tended towards more anodyne sentiments as in “Be My Wife,” “Heroes,” and “DJ,” the last of which hints at Bowie’s decision to focus on the music and distance himself from controversial statements:

I am a D.J., I am what I play.

Can’t turn around no, can’t turn around.

But Bowie’s odyssey was far from over. While the 1970s represented the post-Vietnam weakness of America and the rise of European potentialities, the Eighties marked a revival of American power and influence and a return to its musical tastes and value system, which exerted a strong pull on Bowie’s particular brand of rootlessness.

|

| Bowie at the globalisation of rock |

Bowie’s 1980s albums, especially Let’s Dance, saw him getting heavily into funk, bringing in Nile Rodgers as producer, and embracing the culturally leftist narratives of “one worldism” and boosting the underdog, then common in pop and rock music. This is made clear in the video for the album’s title track, in which its Aboriginal characters are treated sympathetically as they struggle with the world imposed by the White man.

The song “China Girl,” written several years before, plays with fascistic tropes — “I stumble into town just like a sacred cow, visions of swastikas in my head, plans for everyone” — but is replete with self-serving irony, as swastikas are a common sight in the East, being both a Hindu and Buddhist symbol. The song then glamorizes Red China chic while promoting miscegenation.

From this album onwards, Bowie’s significance as a major musical artist declined, but with his Somalian wife (married 1992) and half-Black daughter (born 2002), we see Bowie again echoing other forces acting on Britain and other themes being played out, namely the forces of mass immigration, miscegenation, and increasing marginalization of Whites.

With Bowie’s death, his legacy and his wealth effectively falls into the hands of aliens, emphasising yet again the rootlessness of a Britain that, like Bowie, has gone through a myriad of changes in the last few decades.

_______________

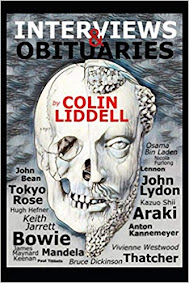

Colin Liddell is the Chief Editor of Neokrat and the author of Interviews & Obituaries, a collection of encounters with the dead and the famous. Support his work by buying it here (USA), here (UK), and here (Australia).